Medicine

- Hospital Charge Variation And Medicare Equipment Fraud: Two Forms Of Gaming The "non-system"

There has been extensive coverage of the recently published report from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that revealed dramatic differences in the prices charged for medical services between hospitals, not only between regions but...

- Would Free Medical Schools Increase Primary Care?

. An op-ed by Peter B. Bach and Robert Kocher in the NY Times March 28, 2011, “Why medical school should be free”, makes a strong argument for just that. They acknowledge that this might seem unreasonable given the fact that physicians, regardless...

- Outing The Ruc: Medicare Reimbursement And Primary Care

. Along with many others, I have written extensively about the need for more primary care physicians in the US. I have also addressed the various disincentives that exist for medical students to enter primary care specialties, such as family medicine,...

- Medicare For All: Moran's Logic, Not The Idea, Is Flawed

. I recently received an email from one of our Kansas Congressmen, Jerry Moran, Republican from the First District that covers essentially the western 2/3 of the state. (He is not my congressman, who is Blue Dog Democrat Dennis Moore, but we are a small...

- Primary Care Shortage Makes Times Front Page

On April 27, 2009 the New York Times ran a page 1, right-column piece entitled “Shortage of Doctors Proves Obstacle to Obama Goals” by Robert Pear.[1] This is very interesting in part because this position in the paper is reserved for the most important...

Medicine

Medicare payments to doctors: the big issue is the underpayment for primary care

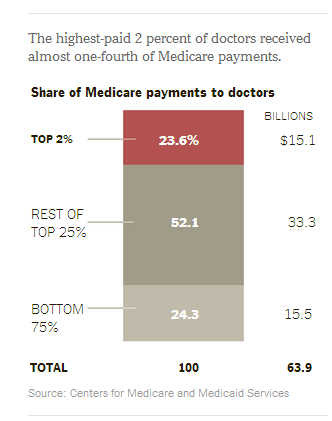

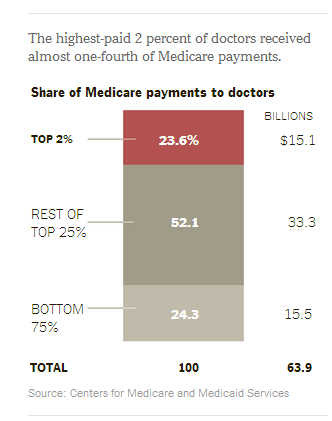

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) just published how much money individual doctors get paid from Medicare. This initial version is without names, but undoubtedly the names will eventually be revealed. Enough information is available for Reed Abelson and Sarah Cohen, who wrote the article for the New York Times on April 9, 2014 “Sliver of Medicare Doctors Get Big Share of Payouts”, to identify many of the specialties and locations. About ¼ of all Medicare payments, the article tells us, go to about 2% of all doctors. “In 2012, 100 doctors received a total of $610 million, ranging from a Florida ophthalmologist who was paid $21 million by Medicare to dozens of doctors, eye and cancer specialists chief among them, who received more than $4 million each that year.” The largest amount of money was accounted for by office visits, $12B, but this was for 214M visits, with an average reimbursement of $57, in contrast to the Florida ophthalmologist, or to the “Fewer than 1,000 radiation oncologists, for example, received payments totaling $1.1 billion.”

Much of the discussion in the article, and in the comments attached, relates to why so few doctors get so much of the $77B Medicare pays out each year. There are, obviously, concerns about fraud; not only is Medicare seemingly fixated on looking for fraud everywhere but there is good evidence that it has occurred, at least historically. For example a highly paid (by Medicare) Florida ophthalmologist is apparently linked to a previous Medicare fraud scandal in which there was some implication of New Jersey Senator Robert Menendez. “The Office of Inspector General for the Department of Health and Human Services, which serves as a federal watchdog on fraud and abuse for the agency, released a report in December recommending greater scrutiny of those physicians who were Medicare’s highest billers.” I would have to say that this is a much wiser, fairer, and probably more productive strategy than simply trying to find largely unintentional errors in coding for outpatient visits, or checking each hospital admission to see if it could have been an “observation”, which is reimbursed less because it is considered outpatient status, as is done by Medicare’s Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs, or as I have called them, bounty hunters). Also, as I have previously discussed, these efforts are harmful to the patient in a direct financial way; as an “outpatient”, a Medicare recipient in the hospital has much higher out-of-pocket costs than if they are admitted as an inpatient. This is, of course, why CMS wishes to limit some stays, but if a person medically needs to be in the hospital, Medicare should pay for a hospitalization, and not play these games that not only financially penalize the hospital and doctors but more importantly the patient.

The other big area discussed is whether, if not exactly fraud, there is substantial difference in practice (e.g., getting CTs before each procedure, using more expensive drugs, etc.) that some specialists who are highly reimbursed by Medicare are doing more of than others. In addition, the question is “are they doing more procedures” or doing procedures with less strict indications? It is worth looking at; there is no guarantee that, even if some doctors are doing more procedures, having looser criteria for them, using more expensive drugs and tests, that this is not the better way to practice, but there is no guarantee that it is the better way to practice. If some doctors are outliers in their specialty, and their practice characteristics “happen” to end up making them a LOT more money than others, then this is certainly a reasonable basis on which to look more closely at how they are practicing, and what is the evidence basis of appropriate practice.

A third issue is that many of the recipients of the most money from Medicare, particularly oncologists (cancer doctors) and ophthalmologists are using very expensive drugs, which they have to buy first and which Medicare reimburses them for. Thus, this skews their reimbursement upward even though the money (or most of it) does not go to the doctor, but rather to the pharmaceutical company. The article refers to a drug called ranibizumab, injected into the eye by ophthalmologists monthly for age-related macular degeneration. It is very expensive, as are many drugs which are made through recombinant DNA (a lot end in “-ab”) used by oncologists, neurologists, rheumatologists, and gastroenterologists as well. One comment notes that he as a physician only makes 3% on the drug. While it can be argued that this is a significant markup (for example, making $3000 on a $100,000 drug), and that this doesn’t include the doctor’s fee for administering it (substantial), it is unfair to count the full cost of the drug as income for the doctor. Of course, it is income for someone (the pharmaceutical company) which suggests there needs to be substantial investigation into pricing of these drugs. And, of course, if a physician is found to be using a lot of a drug where he (or she) makes a 3% markup rather than prescribing an equally effective drug (if there is one) where there is no markup profit, this would be a bad thing.

However, the most important thing revealed by this data, I believe, is the enormously skewed reimbursement by specialty. It is an excellent window into the incredible differences in reimbursement for different specialties, with the ophthalmologists, radiation oncologists, etc. making huge incomes while primary care doctors (and nurse practitioners) are making $57 for an office visit. This is major. The fact that Medicare pays so fantastically much more for procedures (and, as a note, it is likely that all of the doctors, including the 202 family doctors in the highest-paid 2%, are getting it for doing a lot of procedures) leads to private insurers paying similarly more. And makes these specialties very attractive to medical students because they are lucrative (and often, though not in the case of many surgical specialties, involve fewer hours of work). Which leads to fewer primary care doctors, and a dramatic shortage in this country.

Medicare could change this. It could dramatically, not a little bit, change the reimbursement for cognitive visits to be closer to the payment for these procedures. If it did, so would private insurers. If the income of primary care doctors was 70% of that of specialists (instead of say, 30%) data from Altarum researchers and from Canada suggest that the influence of income on specialty choice would largely disappear. More students would enter primary care, and in time we would begin to see a physician workforce that would be closer to what this country needs, about 50% doctors actually practicing primary care.

It is fine if CMS and the OIG look at these highest billing doctors to make sure that they are not committing overt fraud. It is also fine to look at them and see if they are using criteria for procedures that are not supported by current evidence, or doing too many other tests, or taking kickbacks. It is also a good idea to look at the cost of drugs, especially the portion going to the drug company, as well as the markup for physicians, and to re-present the data excluding that portion of the money the doctor does not get (goes to the pharmaceutical company) from their income.

But the most important result of this report should be to be shocked at the way Medicare enables the continued practice of reimbursing for procedures at such high levels, and to kickstart a complete revision of the Medicare fee schedule to bring reimbursement for different specialties into better balance.

That would be a great outcome!

- Hospital Charge Variation And Medicare Equipment Fraud: Two Forms Of Gaming The "non-system"

There has been extensive coverage of the recently published report from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that revealed dramatic differences in the prices charged for medical services between hospitals, not only between regions but...

- Would Free Medical Schools Increase Primary Care?

. An op-ed by Peter B. Bach and Robert Kocher in the NY Times March 28, 2011, “Why medical school should be free”, makes a strong argument for just that. They acknowledge that this might seem unreasonable given the fact that physicians, regardless...

- Outing The Ruc: Medicare Reimbursement And Primary Care

. Along with many others, I have written extensively about the need for more primary care physicians in the US. I have also addressed the various disincentives that exist for medical students to enter primary care specialties, such as family medicine,...

- Medicare For All: Moran's Logic, Not The Idea, Is Flawed

. I recently received an email from one of our Kansas Congressmen, Jerry Moran, Republican from the First District that covers essentially the western 2/3 of the state. (He is not my congressman, who is Blue Dog Democrat Dennis Moore, but we are a small...

- Primary Care Shortage Makes Times Front Page

On April 27, 2009 the New York Times ran a page 1, right-column piece entitled “Shortage of Doctors Proves Obstacle to Obama Goals” by Robert Pear.[1] This is very interesting in part because this position in the paper is reserved for the most important...