Medicine

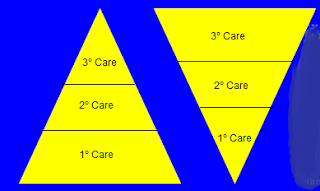

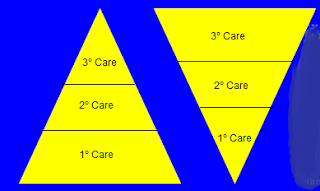

Rust also called for separating the funding for residency training provided by Medicare for primary care from hospital training of subspecialists, arguing that the current system has resulted in "absurd proportions of subspecialists and hospitalists." I have often argued this (for example in GME funding must be targeted to Primary Care, December 10, 2011), noting that hospitals have an interest in training specialists and subspecialists who do things (usually procedures, given our current reimbursement system) that make money for hospitals, and much less for training the primary care doctors that are needed in the community. The problem is that, because academic medical centers provide a great deal of tertiary (and quarternary) care, the mix of primary care and subspecialist and super-subspecialists may be appropriate there, but not for the overall community. However, since these are the places where new physicians are minted and trained, providing the right mix for the community, for the rest of the state and country, means having a very different mix of specialists in training from those working there. This is hard; it is a very common reaction to want to replicate yourself, to want the “best” students to enter training in your specialty, so for an academic medical center which looks like the upside-down pyramid to train doctors in proportion to the right-side-up pyramid is a major challenge! Rust then suggests moving primary care training “back to its community roots”, and says "Instead, let's create direct, sustainable funding for community-based outpatient residency programs that train doctors to keep people out of the hospital”.

Rust also called for separating the funding for residency training provided by Medicare for primary care from hospital training of subspecialists, arguing that the current system has resulted in "absurd proportions of subspecialists and hospitalists." I have often argued this (for example in GME funding must be targeted to Primary Care, December 10, 2011), noting that hospitals have an interest in training specialists and subspecialists who do things (usually procedures, given our current reimbursement system) that make money for hospitals, and much less for training the primary care doctors that are needed in the community. The problem is that, because academic medical centers provide a great deal of tertiary (and quarternary) care, the mix of primary care and subspecialist and super-subspecialists may be appropriate there, but not for the overall community. However, since these are the places where new physicians are minted and trained, providing the right mix for the community, for the rest of the state and country, means having a very different mix of specialists in training from those working there. This is hard; it is a very common reaction to want to replicate yourself, to want the “best” students to enter training in your specialty, so for an academic medical center which looks like the upside-down pyramid to train doctors in proportion to the right-side-up pyramid is a major challenge! Rust then suggests moving primary care training “back to its community roots”, and says "Instead, let's create direct, sustainable funding for community-based outpatient residency programs that train doctors to keep people out of the hospital”.

[1] Sinsky, C, et al.,, “In Search of Joy in Practice: A Report of 23 High-Functioning Primary Care Practices”, Ann Fam Med May/June 2013 vol. 11 no. 3 272-278, doi: 10.1370/afm.1531

- Why Do Students Not Choose Primary Care?

We need more primary care physicians. I have written about this often, and cited extensive references that support this contention, most recently in The role of Primary Care in improving health: In the US and around the world, October 13, 2013. Yet,...

- Training Rural Family Doctors

. In a recent report from the University of Washington’s WWAMI Rural Research Center, “Family Medicine Residency Training in Rural Locations”,[1] Chen et. al. repeat their 2000 study of rural training in the US. They note that this is very important...

- Primary Care: What Takes So Much Time? And How Are We Paying For It?

. In a piece that has gotten a lot of attention, “What’s Keeping Us So Busy in Primary Care? A Snapshot from One Practice”(New England Journal of Medicine, Apr29,2010;362(17):1632-6), Philadelphia general internist Richard J. Baron writes about...

- How Would You Rate Your Health Care Team?

Two recent commentaries in the Annals of Family Medicine and the New England Journal of Medicine argue that the performance of modern family doctors can only be as good as their practice teams. In "The Myth of the Lone Physician: Toward...

- Your Primary Care Team Will See You Now

In a previous post about how health reform will change your doctor's visits, I mentioned that you're likely to see your future primary care delivered by a "team" of health professionals rather than your doctor. You might be surprised to hear that...

Medicine

Helping primary care help the health of all of us

Rust also called for separating the funding for residency training provided by Medicare for primary care from hospital training of subspecialists, arguing that the current system has resulted in "absurd proportions of subspecialists and hospitalists." I have often argued this (for example in GME funding must be targeted to Primary Care, December 10, 2011), noting that hospitals have an interest in training specialists and subspecialists who do things (usually procedures, given our current reimbursement system) that make money for hospitals, and much less for training the primary care doctors that are needed in the community. The problem is that, because academic medical centers provide a great deal of tertiary (and quarternary) care, the mix of primary care and subspecialist and super-subspecialists may be appropriate there, but not for the overall community. However, since these are the places where new physicians are minted and trained, providing the right mix for the community, for the rest of the state and country, means having a very different mix of specialists in training from those working there. This is hard; it is a very common reaction to want to replicate yourself, to want the “best” students to enter training in your specialty, so for an academic medical center which looks like the upside-down pyramid to train doctors in proportion to the right-side-up pyramid is a major challenge! Rust then suggests moving primary care training “back to its community roots”, and says "Instead, let's create direct, sustainable funding for community-based outpatient residency programs that train doctors to keep people out of the hospital”.

Rust also called for separating the funding for residency training provided by Medicare for primary care from hospital training of subspecialists, arguing that the current system has resulted in "absurd proportions of subspecialists and hospitalists." I have often argued this (for example in GME funding must be targeted to Primary Care, December 10, 2011), noting that hospitals have an interest in training specialists and subspecialists who do things (usually procedures, given our current reimbursement system) that make money for hospitals, and much less for training the primary care doctors that are needed in the community. The problem is that, because academic medical centers provide a great deal of tertiary (and quarternary) care, the mix of primary care and subspecialist and super-subspecialists may be appropriate there, but not for the overall community. However, since these are the places where new physicians are minted and trained, providing the right mix for the community, for the rest of the state and country, means having a very different mix of specialists in training from those working there. This is hard; it is a very common reaction to want to replicate yourself, to want the “best” students to enter training in your specialty, so for an academic medical center which looks like the upside-down pyramid to train doctors in proportion to the right-side-up pyramid is a major challenge! Rust then suggests moving primary care training “back to its community roots”, and says "Instead, let's create direct, sustainable funding for community-based outpatient residency programs that train doctors to keep people out of the hospital”. As strong as Dr. Rust’s arguments are, primary care will still have problems. One of the comments on the posting at the “AAFP News Brief” that covered this testimony said “I must be missing something. Can anyone explain how creating more residency slots will increase med student interest in family medicine?” I believe that this is an excellent point – if we cannot fill the slots that exist today for family medicine, particularly with excellent medical students, how will increasing the number of slots improve things? One of the answers, certainly involves reimbursement, dramatically decreasing the difference between what primary care doctors earn and what more highly-paid subspecialists earn; work by the Altarum Institute cited by Jerry Kruse, MD MSPH in his article “Income Ratio and Medical Student Specialty Choice: The Primary Importance of the Ratio of Mean Primary Care Physician Income to Mean Consulting Specialist Income”, suggest that the ratio should be about 80%.

However, there are other factors at work. Sometimes they are referred to as “lifestyle” (perhaps defined as hours of work needed to generate a certain income, or what I have called the income/work hours ratio) but they are more profound than that. In the May/June issue of the Annals of Family Medicine, Christine Sinsky and her colleagues refer to it as “the joy of practice”. “In Search of Joy in Practice: A Report of 23 High-Functioning Primary Care Practices” [1] identifies the “deep dissatisfaction” experienced by primary care physicians who care for adults (general internists and family physicians) demonstrated by the many reports of high “burnout” rates. The authors relate this to the extraordinary amount of time that physicians spend doing paperwork and administrative functions, and the pressure by employers to generate high numbers of visits; doctors experience this as alienating and not the reason that they became physicians.

“We propose joy in practice as a deliberately provocative concept to describe what we believe is missing in the physician experience of primary care. The concept of physician satisfaction suggests innovations that are limited to tweaking compensation or panel size. If, however, as the literature suggests, physicians seek out the arduous field of medicine, and primary care in particular, as a calling because of their desire to create healing relationships with patients, then interventions must go far deeper. Joy in practice implies a fundamental redesign of the medical encounter to restore the healing relationship of patients with their physicians and health care systems. Joy in practice includes a high level of physician work life satisfaction, a low level of burnout, and a feeling that medical practice is fulfilling.”

The authors go on to list a number of common problems, and solutions that have been found by one or more of the 23 practices that they visited and analyzed in detail. They included:

· Reducing work through pre-visit planning and pre-appointment laboratory tests;

· Adding capacity by sharing the care among the team;

· Eliminating time-consuming documentation through in-visit scribing and assistant order entry;

· Saving time by re-engineering prescription renewal work out of the practice;

· Reducing unnecessary physician work through in-box management;

· Improving team communication through co-location, huddles and team meetings;

· Improving team functioning through systems planning and workflow mapping.

These are all good ideas, and the solutions are sometimes creative, sometimes painfully obvious, and sometimes obstructed by our bizarre health system. One of my favorites, the second, is an example of the latter:

“We observed that team development must often overcome an anti–team culture. Institutional policies (only the doctor can perform order entry), regulatory constraints (only the physician can sign paperwork for hearing aid batteries, meals delivery, or durable medical equipment), technology limitations (electronic health record work flows are designed around physician data entry), and payment policies that only reimburse physician activity constrain teams in their efforts to share the care. An extended care team of a social worker, nutritionist, and pharmacist may be affordable only in practices with external funding or global budgeting.”

Thus is illustrated the tie-in between innovations that can make practice again joyful and the payment reform and re-working of our entire non-system which we desperately need! There is a long way to go; as the authors point out, no single practice has solved every problem. But the linkage is clear – a medical care system designed to reward expensive interventions for a relatively small number of people has created an inappropriate mixture of physicians as well as an incentive for hospitals to focus mainly on such procedures, as it has increased the burden on, and in many cases taken the joy out of, being a primary care physician. It is important to remember that it is not just about the doctors (I try to remind my students and residents, precious as each of them are to themselves and their families and often to me, that ultimately it is not about them). The authors put it this way:

“The current practice model in primary care is unsustainable. We question why young people would devote 11 years preparing for a career during which they will spend a substantial portion of their work days, as well as much of their personal time at nights, on form-filling, box-ticking, and other clerical tasks that do not utilize their training. Likewise, we question whether patients benefit when their physicians spend most of their work effort on such tasks. Primary care physician burnout threatens the quality of patient care, access, and cost-containment within the US health care system.”

Both the macro-structural changes in the structure of the system as identified by Dr. Rust and the more micro-level changes in the practices of primary care clinicians identified by Dr. Sinsky and colleagues need to occur to make us have a sustainable, healthful, system of health care. And they need to happen soon.

[1] Sinsky, C, et al.,, “In Search of Joy in Practice: A Report of 23 High-Functioning Primary Care Practices”, Ann Fam Med May/June 2013 vol. 11 no. 3 272-278, doi: 10.1370/afm.1531

- Why Do Students Not Choose Primary Care?

We need more primary care physicians. I have written about this often, and cited extensive references that support this contention, most recently in The role of Primary Care in improving health: In the US and around the world, October 13, 2013. Yet,...

- Training Rural Family Doctors

. In a recent report from the University of Washington’s WWAMI Rural Research Center, “Family Medicine Residency Training in Rural Locations”,[1] Chen et. al. repeat their 2000 study of rural training in the US. They note that this is very important...

- Primary Care: What Takes So Much Time? And How Are We Paying For It?

. In a piece that has gotten a lot of attention, “What’s Keeping Us So Busy in Primary Care? A Snapshot from One Practice”(New England Journal of Medicine, Apr29,2010;362(17):1632-6), Philadelphia general internist Richard J. Baron writes about...

- How Would You Rate Your Health Care Team?

Two recent commentaries in the Annals of Family Medicine and the New England Journal of Medicine argue that the performance of modern family doctors can only be as good as their practice teams. In "The Myth of the Lone Physician: Toward...

- Your Primary Care Team Will See You Now

In a previous post about how health reform will change your doctor's visits, I mentioned that you're likely to see your future primary care delivered by a "team" of health professionals rather than your doctor. You might be surprised to hear that...