Medicine

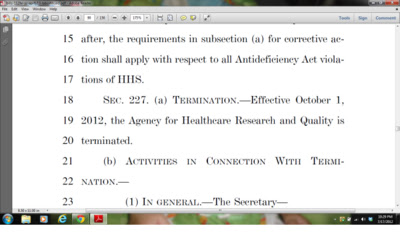

The health services research world is reeling today from the inclusion of draft language in a House of Representatives appropriations bill that would eliminate the entire budget of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality starting on October 1, 2012. Below is a screenshot from page 90 of the bill:

As most readers know, I was employed by AHRQ from 2006 to 2010, as a Medical Officer supporting the work of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which recently recommended against PSA screening for prostate cancer on the grounds that the downstream harms of the service outweigh any potential benefits. As documented in an October 2011 New York Times Magazine story, the USPSTF deliberately withheld its initial conclusions on PSA screening, fearing a politically-driven backlash against it and AHRQ. Despite the long delay, as well as a carefully orchestrated scientific communications campaign that enlisted the support of powerful allies such as the American Cancer Society's chief medical officer, Otis Brawley, the Agency once again finds itself at death's door. (For an in-depth history of AHRQ's first near-death experience in the mid-1990s at the hands of back surgeons and their supporters, read this Health Affairs article.)

As most readers know, I was employed by AHRQ from 2006 to 2010, as a Medical Officer supporting the work of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which recently recommended against PSA screening for prostate cancer on the grounds that the downstream harms of the service outweigh any potential benefits. As documented in an October 2011 New York Times Magazine story, the USPSTF deliberately withheld its initial conclusions on PSA screening, fearing a politically-driven backlash against it and AHRQ. Despite the long delay, as well as a carefully orchestrated scientific communications campaign that enlisted the support of powerful allies such as the American Cancer Society's chief medical officer, Otis Brawley, the Agency once again finds itself at death's door. (For an in-depth history of AHRQ's first near-death experience in the mid-1990s at the hands of back surgeons and their supporters, read this Health Affairs article.)

For those of you who may be unfamiliar with AHRQ and the benefits of the research it supports, below is a Healthcare Headaches blog post I wrote last year for USNews.com. Its message is even more relevant now than it was then. Please call your Congressmen and women, spread the word to friends and colleagues, and help #SaveAHRQ from a fate that would have devastating effects on the future health of our nation.

**

When a new drug goes on the market for, say, diabetes, doctors are typically bombarded by advertising messages that promote it. Patients may see television commercials touting the new drug’s advantages over older ones and advising them to "talk to your doctor" about obtaining a prescription. But since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration only requires drug companies to prove that new drugs work better than placebos (sugar pills), there’s often little or no reliable information about whether a new drug is actually an improvement over existing therapies.

How, then, can a doctor like me make good choices about which treatment to give each patient? To provide answers, last year's health reform law devoted billions of dollars over the next decade to "comparative effectiveness" research, or research that directly compares different tests and treatments to determine which are better at improving health in particular groups of patients.

Funding for comparative effectiveness studies was recently targeted for budget cuts by politicians who argue that such research may limit patients' treatment choices and lead to the withdrawal of insurance coverage for drugs that are found to be costly or ineffective. In reality, however, that’s not necessarily the case. For example, when the FDA recently concluded that the cancer drug Avastin does not help patients with breast cancer (and often causes serious side effects such as bleeding, heart attacks, and heart failure), officials were quick to assure the public that the Medicare program will continue to pay for it anyway.

What has been lost in the political debate is the value of comparative effectiveness studies in helping doctors and patients make better treatment decisions. For example, the Effective Health Care Program at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which sponsors comparative effectiveness research for many conditions that I commonly treat among my patients, recently published a patient-friendly guide to medicines for type 2 (adult-onset) diabetes that clearly spells out the advantages and disadvantages of the many drugs available to lower blood sugar. Patients can read this guide online or print out a copy to take with them to their doctor. (Full disclosure: I am a former employee of AHRQ, but was not involved with this program.)

Also, in a 2009 study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic researchers concluded that a "decision aid" for patients with diabetes based on a previous version of the AHRQ medication guide improved patients' knowledge and involvement in their care. This decision aid consisted of six flash cards containing basic information about the effects of five types of diabetes drugs on weight change, blood sugar levels, side effects, and ease of use (when to take it and how often blood sugar testing is required).

In a highly charged political environment, it’s tempting to score points (and scare patients) by falsely equating comparative effectiveness research with “rationing.” But I believe that the valuable information obtained from this research, rather than restricting patients' treatment options, will instead empower them and their doctors to make better decisions about their health care.

- Comparative Effectiveness Research

. I’m a doctor, so maybe I have a different take on this than other people, but somehow I don’t think so. I would imagine most folks would want to know, before being put on a new, expensive medication (and in medications, “new” virtually always...

- Clinical Guidelines And Technology Assessment

“Clinical Guidelines and Technology Assessment”? Well, there’s a yawner! Maybe you'll be one of the few who won’t say “I think I’ll skip this one”, but if you are not, I’d have to be empathic. I’m thinking about the time I picked...

- Politics And Practice Guidelines: A Volatile Mix

Health services research in the United States has historically been the "poor cousin" of biomedical research in federal funding and support. The annual budget for the National Institutes of Health, for example, is typically around 100 times that of the...

- Psa Testing: Will Science Finally Trump Politics?

Maybe the third time will finally be the charm.In early November 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force voted unanimously to update its 15-month old recommendations on screening for prostate cancer in men younger than 75, changing its previous...

- "politics Trumped Science": Breast Cancer Chemoprevention

On November 17, 2009, in the same issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine that contained the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force's controversial new recommendations on screening for breast cancer, the journal also published a report on the comparative...

Medicine

How politically unpopular research from AHRQ helps us make better medical decisions

The health services research world is reeling today from the inclusion of draft language in a House of Representatives appropriations bill that would eliminate the entire budget of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality starting on October 1, 2012. Below is a screenshot from page 90 of the bill:

For those of you who may be unfamiliar with AHRQ and the benefits of the research it supports, below is a Healthcare Headaches blog post I wrote last year for USNews.com. Its message is even more relevant now than it was then. Please call your Congressmen and women, spread the word to friends and colleagues, and help #SaveAHRQ from a fate that would have devastating effects on the future health of our nation.

**

When a new drug goes on the market for, say, diabetes, doctors are typically bombarded by advertising messages that promote it. Patients may see television commercials touting the new drug’s advantages over older ones and advising them to "talk to your doctor" about obtaining a prescription. But since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration only requires drug companies to prove that new drugs work better than placebos (sugar pills), there’s often little or no reliable information about whether a new drug is actually an improvement over existing therapies.

How, then, can a doctor like me make good choices about which treatment to give each patient? To provide answers, last year's health reform law devoted billions of dollars over the next decade to "comparative effectiveness" research, or research that directly compares different tests and treatments to determine which are better at improving health in particular groups of patients.

Funding for comparative effectiveness studies was recently targeted for budget cuts by politicians who argue that such research may limit patients' treatment choices and lead to the withdrawal of insurance coverage for drugs that are found to be costly or ineffective. In reality, however, that’s not necessarily the case. For example, when the FDA recently concluded that the cancer drug Avastin does not help patients with breast cancer (and often causes serious side effects such as bleeding, heart attacks, and heart failure), officials were quick to assure the public that the Medicare program will continue to pay for it anyway.

What has been lost in the political debate is the value of comparative effectiveness studies in helping doctors and patients make better treatment decisions. For example, the Effective Health Care Program at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which sponsors comparative effectiveness research for many conditions that I commonly treat among my patients, recently published a patient-friendly guide to medicines for type 2 (adult-onset) diabetes that clearly spells out the advantages and disadvantages of the many drugs available to lower blood sugar. Patients can read this guide online or print out a copy to take with them to their doctor. (Full disclosure: I am a former employee of AHRQ, but was not involved with this program.)

Also, in a 2009 study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic researchers concluded that a "decision aid" for patients with diabetes based on a previous version of the AHRQ medication guide improved patients' knowledge and involvement in their care. This decision aid consisted of six flash cards containing basic information about the effects of five types of diabetes drugs on weight change, blood sugar levels, side effects, and ease of use (when to take it and how often blood sugar testing is required).

In a highly charged political environment, it’s tempting to score points (and scare patients) by falsely equating comparative effectiveness research with “rationing.” But I believe that the valuable information obtained from this research, rather than restricting patients' treatment options, will instead empower them and their doctors to make better decisions about their health care.

- Comparative Effectiveness Research

. I’m a doctor, so maybe I have a different take on this than other people, but somehow I don’t think so. I would imagine most folks would want to know, before being put on a new, expensive medication (and in medications, “new” virtually always...

- Clinical Guidelines And Technology Assessment

“Clinical Guidelines and Technology Assessment”? Well, there’s a yawner! Maybe you'll be one of the few who won’t say “I think I’ll skip this one”, but if you are not, I’d have to be empathic. I’m thinking about the time I picked...

- Politics And Practice Guidelines: A Volatile Mix

Health services research in the United States has historically been the "poor cousin" of biomedical research in federal funding and support. The annual budget for the National Institutes of Health, for example, is typically around 100 times that of the...

- Psa Testing: Will Science Finally Trump Politics?

Maybe the third time will finally be the charm.In early November 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force voted unanimously to update its 15-month old recommendations on screening for prostate cancer in men younger than 75, changing its previous...

- "politics Trumped Science": Breast Cancer Chemoprevention

On November 17, 2009, in the same issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine that contained the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force's controversial new recommendations on screening for breast cancer, the journal also published a report on the comparative...